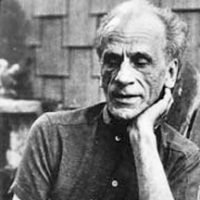

Joseph Cornell (December 24, 1903 – December 29, 1972) was an American artist and sculptor, one of the pioneers and most celebrated exponents of assemblage. Influenced by the Surrealists, he was also an avant-garde experimental filmmaker. Joseph Cornell was born in Nyack, New York, to Joseph Cornell, a well-to-do designer and merchant of textiles, and Helen TenBroeck Storms Cornell, who had trained as a kindergarten teacher. The Cornells had four children: Joseph, Elizabeth (b. 1905), Helen (b. 1906), and Robert (b. 1910). Both parents came from socially prominent families of Dutch ancestry, long-established in New York State. Cornell’s father died in 1917, leaving the family in straitened circumstances. Following the elder Cornell’s death, his wife and children moved to the borough of Queens in New York City. Cornell attended Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, in the class of 1921, although he did not graduate. Except for the three and a half years he spent at Phillips, he lived for most of his life in a small, wooden-frame house on Utopia Parkway in a working-class area of Flushing, along with his mother and his brother Robert, whom cerebral palsy had rendered physically challenged.

Cornell was wary of strangers. This led him to isolate himself and become a self-taught artist. Although he expressed attraction to unattainable women like Lauren Bacall, his shyness made romantic relationships almost impossible. In later life his bashfulness verged toward reclusiveness, and he rarely left the state of New York. However, he preferred talking with women, and often made their husbands wait in the next room when he discussed business with them. He also had numerous friendships with ballerinas, who found him unique, but too eccentric to be a romantic partner.

His last major exhibition was a show he arranged especially for children, with the boxes displayed at child height and with the opening party serving soft drinks and cake.

He devoted his life to caring for his younger brother Robert, an invalid suffering from cerebral palsy. This was another factor in his lack of relationships. At some point in the 1920s, or possibly earlier, he read the writings of Mary Baker Eddy. Her works, including Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures, Cornell considered being among the most important books ever published after the Bible, and he became a lifelong Christian Science adherent. He was also rather poor for most of his life, working during the 1920s as a wholesale fabric salesman to support his family. As a result of the American Great Depression, Cornell lost his textile industry job in 1931, and worked for a short time thereafter as a door-to-door appliance salesman. During this time, through her friendship with Ethel Traphagen, Cornell’s mother secured him a part-time position designing textiles. In the 1940s, Cornell also worked in a plant nursery (which would figure in his famous dossier “GC44”) and briefly in a defense plant, and designed covers and feature layouts for Harper’s Bazaar, View, Dance Index, and other magazines. He only really began to sell his boxes for significant sums after his 1949 solo show at the Charles Egan Gallery.

Cornell became a highly regarded artist towards the end of his career, yet remained out of the spotlight. He produced fewer box assemblages in the 1950s and 1960s, as his family responsibilities increased and claimed more of his time. He hired a series of young assistants, including both students and established artists, to help him organize material, make artwork, and run errands. At this time, Cornell concentrated on making collages, and collaborated with filmmakers like Rudy Burckhardt, Stan Brakhage, and Larry Jordan to make films that were evocative of moving collages.

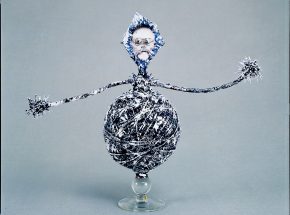

Cornell’s brother Robert died in 1965, and his mother in 1966. Joseph Cornell died of apparent heart failure on 29 December 1972, a few days after his sixty-ninth birthday. The executors of his estate were Richard Ader and Wayne Andrews, as represented by the art dealers Leo Castelli, Richard Feigen, and James Corcoran. Later the Joseph and Robert Cornell Memorial Foundation was established, which administers the copyrights of Cornell’s works and represents the interests of his heirs. Cornell’s most characteristic art works were boxed assemblages created from found objects. These are simple boxes, usually fronted with a glass pane, in which he arranged surprising collections of photographs or Victorian bric-à-brac, in a way that combines the formal austerity of Constructivism with the lively fantasy of Surrealism. Many of his boxes, such as the famous Medici Slot Machine boxes, are interactive and are meant to be handled. Like Kurt Schwitters, Cornell could create poetry from the commonplace. Unlike Schwitters, however, he was fascinated not by refuse, garbage, and the discarded, but by fragments of once beautiful and precious objects he found on his frequent trips to the bookshops and thrift stores of New York. His boxes relied on the Surrealist technique of irrational juxtaposition, and on the evocation of nostalgia, for their appeal. Cornell never regarded himself as a Surrealist; although he admired the work and technique of Surrealists like Max Ernst and René Magritte, he disavowed the Surrealists’ “black magic,” claiming that he only wished to make white magic with his art. Cornell’s fame as the leading American “Surrealist” allowed him to befriend several members of the Surrealist movement when they settled in the USA during the Second World War. Later he was claimed as a herald of pop art and installation art.

Cornell often made series of boxed assemblages that reflected his various interests: the Soap Bubble Sets, the Medici Slot Machine series, the Pink Palace series, the Hotel series, the Observatory series, and the Space Object Boxes, among others. Also captivated with birds, Cornell created an Aviary series of boxes, in which colorful images of various birds were mounted on wood, cut out, & set against harsh white backgrounds.

In addition to creating boxes and flat collages and making short art films, Cornell also kept a filing system of over 160 visual-documentary “dossiers” on themes that interested him; the dossiers served as repositories from which Cornell drew material and inspiration for boxes like his “penny arcade” portrait of Lauren Bacall. He had no formal training in art, although he was extremely well read and was conversant with the New York art scene from the 1940s through to the 1960s.

Cornell was heavily influenced by the American Transcendentalists, Hollywood starlets (to whom he sent boxes he had dedicated to them), the French Symbolists such as Stéphane Mallarmé and Gérard de Nerval, and great dancers of the 19th century ballet such as Marie Taglioni and Fanny Cerrito.

Christian Science belief and practice informed Cornell’s art deeply, as art historian Sandra Leonard Starr has shown.

Joseph Cornell’s 1936 found-film montage Rose Hobart was made entirely from splicing together existing film stock that Cornell had found in New Jersey warehouses, mostly derived from a 1931 ‘B’ film entitled East of Borneo. Cornell would play Nestor Amaral’s record, ‘Holiday in Brazil’ during its rare screenings, as well as projecting the film through a deep blue glass or filter, giving the film a dreamlike effect. Focusing mainly on the gestures and expressions made by Rose Hobart (the original film’s starlet), this dreamscape of Cornell’s seems to exist in a kind of suspension until the film’s most arresting sequence toward the end, when footage of a solar eclipse is juxtaposed with a white ball falling into a pool of water in slow motion.

Cornell premiered the film at the Julien Levy Gallery in December 1936 during the first Surrealist exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Salvador Dalí, who was in New York to attend the MoMA opening, was present at its first screening. During the screening, Dali became outraged at Cornell’s movie, claiming he had just had the same idea of applying collage techniques to film. After the screening, Dali remarked to Cornell that he should stick to making boxes and to stop making films. Traumatized by this event, the shy, retiring Cornell showed his films rarely thereafter.

Joseph Cornell continued to experiment with film until his death in 1972. While his earlier films were often collages of found short films, his later ones montaged together footage he expressly commissioned from the professional filmmakers with whom he collaborated. These latter films were often set in some of Cornell’s favorite neighborhoods and landmarks in New York City: Mulberry Street, Bryant Park, Union Square Park, and the Third Avenue Elevated Railway, among others.

In 1969 Cornell gave a collection of both his own films and the works of others to Anthology Film Archives in New York City.

www.en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_Cornell