William Herbert Dunton, known later in life as “Buck,” was born in Augusta, Maine, in 1878. His lifelong passion for the outdoors was nurtured from an early age by his grandfather, who took him on expeditions, teaching him about hunting and fishing. Drawing the outdoors followed naturally. As a child, Dunton was self-taught, developing a precise style that would lead to a successful career as an illustrator. He first sold drawings to a magazine at age 16, when he quit school to work as a professional illustrator.

Dunton’s precocious talent was further educated with classes at the Cowles Art School in Boston, and at the Art Student’s League in New York City. The magazines that Dunton worked for included Harper’s Weekly, Collier’s, Woman’s Home Companion, Scribners, Cosmopolitan, and several others. He also illustrated numerous books, including several of the classic cowboy stories of Zane Grey. It was the search for subject material for illustrations of western life that first brought Dunton out West, to Montana, in 1896. For the next 15 years, he spent every summer traveling the western states, doing sketches that would become the basis for his magazine illustrations. It was during this period that Dunton began to grow weary, and eventually fed up with the pressures of deadlines, and the demands of editors.

Meanwhile in 1900, Dunton married Nellie G. Hartley of Waltham, Massachusetts. He returned with his bride to Montana the following year. A bunkhouse served the couple as a honeymoon retreat. Dunton already had made contacts by this time with publishers in New York City. As early as 1899 his illustrations had begun appearing in the National Sportsman and Nickell Magazine. He illustrated his first book in 1902.

In 1903 the Duntons moved to New York City, where Dunton shared a studio with another young artist, Carl Schwab. In 1905 they moved again to Ridgewood, New Jersey, where their first child was born. The Duntons had four children between 1905 and 1913. Two survived, a daughter Vivian and a son Ivan. Both of them appear in Dunton’s later paintings. Meanwhile in 1908 Dunton was elected to membership in the Salmagundi Club, a social club for artists in New York, whose membership included several of Dunton’s future Taos colleagues, notably Berninghaus, Blumenschein, Couse, Bert Phillips, and Walter Ufer.

In New York City, Dunton continued to work for such magazines as National Sportsman. He illustrated a number of short stories, including several of his own. From about 1902 he began illustrating serialized features and then novels by Hamlin Garland, E. B. Bronson, and Zane Grey. At the same time Dunton’s paintings appeared frequently on the covers of the nation’s leading periodicals, including Harper’s Weekly, Collier’s, Saturday Evening Post, Cosmopolitan, and McClure’s magazines. It was one of the most prolific as well as demanding periods of his life.

Winters in New York tended to drain him of energy and ideas, and Dunton spent longer periods of time each year in the West seeking new inspiration for his work. Between trips, when he could find the time, he enrolled in classes at the Art Students League. In 1911 Dunton again encountered E. L. Blumenschein at the Art Students League, where Blumenschein was teaching a class. Recognizing Dunton’s ability and the direction of his interests, Blumenschein encouraged him to visit Taos, New Mexico, where Blumenschein himself already had discovered a rich source of subject matter.

Dunton visited Taos for the first time in 1912. With Nellie and their two children, he moved there in 1914, occupying a succession of studios until 1923, when he bought a house on what was then the edge of town. With the other charter members of the Taos Society of Artists, Dunton regularly exhibited in shows in Santa Fe from 1915 through 1917 and afterward in New York. Victor Higgins and Walter Ufer joined the group in 1919.

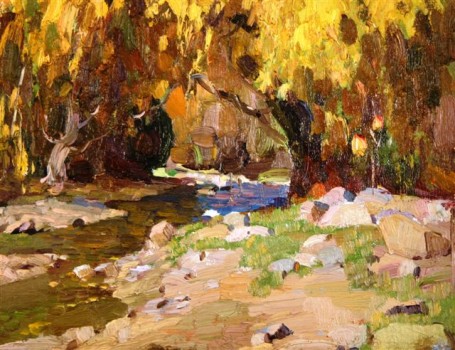

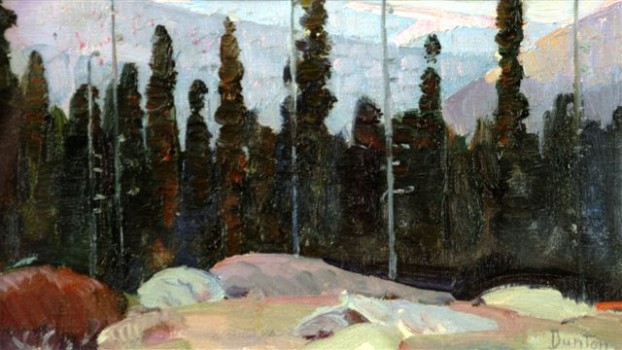

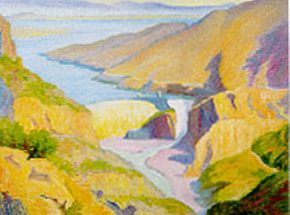

Dunton did not spend all of his time in the studio or on the road promoting exhibitions of his pictures. In his constant search for fresh material, he often camped out for days and even weeks at a time in the mountains near Taos, painting landscapes and wildlife, hunting and sketching in all kinds of weather, at all seasons of the year. He apparently required only a minimum of equipment to sustain him on these outings: a gun, bedroll, cooking gear, sketchbooks, pencils, and paint box. Wholly absorbed in his work, Dunton had little time for anything else.

Nellie did not share Dunton’s love of the outdoor life and found Taos to be a dull, out-of-the way place offering few material or social advantages. Managing a household and family almost single-handedly finally wore her down. Dunton later said that she “cared nothing for art”. At that, the marriage lasted for nearly twenty years before Nellie took the children and moved to Albuquerque, where she made another life for herself. She kept the children with her until about 1921 or 1922, when they began spending summer vacations with their father in Taos.

In 1922 Dunton resigned from the Taos Society of Artists, likely due to a personal conflict, and from then on arranged solo exhibitions of his work. For the next 13 years he exhibited in several states, from New Mexico to New York. In 1923 he was commissioned to do a three paneled mural for the Missouri State Capitol.

Dunton’s health began its long decline in 1928, when he was injured by a horse, and began suffering from ulcers. He continued to deteriorate, and was finally diagnosed with prostate cancer in 1935. Buck Dunton died in Taos in 1936, at the age of 57.

www.kosharehistory.org/museum/dunton.html

Website

http://www.buckdunton.com/